“Relieving the burden of . . . unattainable ideals”

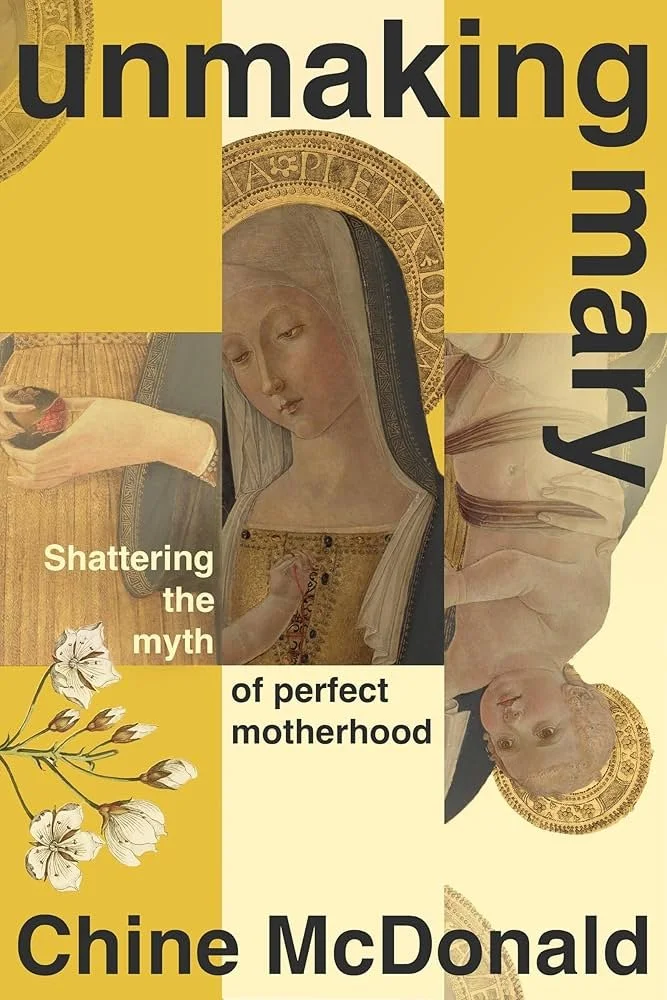

A review of Unmaking Mary: Shattering the Myth of Perfect Motherhood by Chine McDonald (Hodder Faith, 2025)

by Elizabeth Harlan-Ferlo

256 pp., hardcover, $22.99

July 8, 2025

Hodder Faith

ISBN: 978-1399814638

In Unmaking Mary: Shattering the Myth of Perfect Motherhood, Chine McDonald draws on sociological criticism, fresh theological responses, and her own motherhood to examine the role of Mary for mothers and the faithful. She writes, “motherhood is an experience so earth-shattering that it can cause us to rethink all we have thought before, including what it is to be human, who God is, and for some, whether indeed they believe in God or not.” I wish I could have read such a direct and inclusive statement when I was pregnant and raising toddlers. I’m very glad to read Unmaking Mary now.

McDonald organizes her writing around the liturgical life of Mary, with her chapters arranged into sections called “Annunciation,” “Conception,” “Labor,” “Death,” and “Assumption.” She begins with a brief overview of the theological, social, and literary character of Mary in religious culture, and then quickly moves to discuss the effects of that character on women and mothers. McDonald’s references are in abundance and the endnotes build their own syllabus. In this way, the book creates a community of voices around narratives of Mary and motherhood through the ages.

One of the first highlights of her inquiry is a consideration of Mary’s role in the relationship to the gender of God. She proposes that while “the mother of God has been used as a placeholder to contain all the attributes of a female deity that are lost when all you have is a patriarchal God,” Mary herself has been “misunderstood, her femaleness reduced to a one-dimensional view of womanhood and motherhood.” McDonald thus asserts that Marian piety often looks like a reallocation of the feminine divinity from its rightful place within God, largely because of Christianity’s patriarchal legacy. She is savvy in alerting us to the ways Mary has been oversimplified to a set of traits that patriarchy favors, arguing, “Though we may have good intentions when we talk about embracing a more expansive understanding of the gender of God, we risk falling into the trap of reinforcing binaries if our male descriptions of God resemble stereotypes of men, and our female descriptions of God resemble stereotypes of women.”

McDonald lifts up Mary as the first devotee to the study of the Word and a mother who educated her son to live into the vision of her famous Magnificat.

Unmaking Mary offers a corrective to this flattening of Mary. Her role as a movement leader, commonly celebrated in the early church, has since been suppressed into the role of a Victorian “Angel in the House,” a role which McDonald discusses at length in the “Mother Superior” chapter. She also lifts up Mary as the first devotee to the study of the Word and a mother who educated her son to live into the vision of her famous Magnificat. Like many mothers, McDonald feels extraordinarily well-versed in every detail of her children’s likes and dislikes, their bodies and needs. “Of course Mary would have been the same with Jesus, the subject of her maternal thesis,” McDonald writes, “but like any mother, not only was she shaped by her knowledge of him, but she too shaped him.”

McDonald’s most integrated argument is in her chapter on The Black Madonna, named for the prominent iconographic depictions of Mary and her son with dark skin that appear throughout Catholic and Orthodox Europe. As a Black woman herself, McDonald describes racism’s effects inside and outside of the church with a keen understanding. She writes, “It is understandable that Black women—who live with the generational trauma of slavery—might feel uncomfortable bowing at the feet of a nice white Mary who resembles a slave-holding mistress. Unmaking Mary requires us to separate the mother of God from her falsely constructed whiteness, and what it might represent.” Furthermore, McDonald argues the Black Madonna’s intercession and appeal is not exclusive to a single community. In fact, the unconventionality of Black Madonnas “makes them also a useful lens through which to look at ways of mothering that do not fit the archetype either: adoptive mothers, single mothers, older mothers, LGBTQ+ and others.” This image of Mary speaks, in her essence, to the women suffering in motherhood: “It is among these broken fragments of the struggle of mothers that the Black Madonna opens her arms and welcomes in the tired, the sad, the oppressed, the subjugated.”

McDonald offers arresting descriptions of her own experience of pregnancy and motherhood, and she builds her theology around the experience itself: “It was while I was staring into the bottom of the toilet bowl that I saw the face of Jesus and recognized the concept of sacrifice and also what it meant for Mary to bear God in her womb–for her organs to be displaced to grow the God-child; for her body to change in irrevocable ways. Here the theological concept of kenosis—Christ emptying himself out on the cross for the sake of humankind—began to take on new meaning for me.”

McDonald understands the challenges of this claim in a misogynist society where women are regularly expected to pour out themselves for others, especially for their children. “The idea of decentering the mother for the sake of the baby is complicated and needs to be nuanced. We should not ignore the societal misogyny that calls for mothers to empty, diminish or make themselves voices for the sake of their babies.” Clearly McDonald is a practiced theologian and sociologist, and moments like this in Unmaking Mary made me wish that she had discussed this social critique in more depth.

McDonald also offers a theological approach to the Body of Christ and to the Trinity via the experience of pregnancy. “When my children grew in my womb,” she writes, “I felt both one with them and separate from them, our oneness and twoness expressing something of the ineffability of our connection with others in the Body of Christ.” This exploration into Christian doctrine is quite welcome in a book not directly concerned with theological inquiry. While the text tends toward the sociological, more direct theological connections with contemporary understandings of the experience of motherhood are unique and appreciated in concert together.

From Beyoncé to Pope Joan, to Quiverfull movement to Demi Moore’s 1991 Vanity Fair cover, McDonald includes it all. She approaches the intersections of “tradwives”—both religious and secular—and the intersection of this culture with pregnancy and social media. Her call to unmake Mary is partly based on what she has witnessed: “Mary’s perceived powerfulness and passivity—shaped by the ways in which men predominantly have told her story for centuries—does not seem to be as attractive or relevant to young women today.” After describing her own challenges with social media and the drive to appear perfect, McDonald says, “The unmaking of the myth of perfect motherhood will require all of us, me included, to intentionally choose to live more authentically—both offline and online.” At moments like this, I hoped that she would address familiar social criticism with direct theological rejoinder or methodology, especially one directly involving Mary. She does, however, push the Church to enter the conversations around physical perfection and social media pressure for mothers, in part, by unmaking the received Mary image. “What if the Church could be known for playing a part in making space for mothers to come together and share their lows as well as their highs?” McDonald writes, “It could go some way toward relieving the burden of striving for unattainable ideals.”

It is rare to find a book on motherhood that engages so wisely with theology and its sociological implications while at the same time giving a window into the author’s own experiences. By attempting to survey such a broad field, Unmaking Mary can feel exciting in its freshness and sometimes frustrating in its breadth. With McDonald’s text as a beginning, I look forward to the various ways we can re-make Mary for mothers and for all of us.

Elizabeth Harlan-Ferlo is a poet, educator, faith leader, and caregiver. . Her poetry, reviews, and essays have appeared in many literary journals and magazines including The Christian Century, Anglican Theological Review, and The Windover. Her debut poetry collection, Incarnation Again, was published in 2022. Elizabeth serves as Canon for Spirituality Education and Arts at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Portland, Oregon.