As the Mind Dissolves

by Chris Weigel

The plant died. RIP.

When you take care of someone with dementia, the material world can be so confusing.

No one in my house has a smartwatch, yet one day, on the windowsill behind the kitchen sink, a broken smartwatch case appeared in the pot of an ailing plant. My mom must have brought it in the house somehow, but the reason is forever lost to time.

Sometimes the material world can also be terrifying. Yesterday, awake before it was light, the world still, I walked downstairs, and I heard a screeching sound coming from somewhere near my mom’s room. The sound made me feel like I was in an Edgar Allan Poe horror story, where, instead of a beating heart, I heard what fingernails would sound like if they became sentient as they went down a flaming chalkboard.

I thought it sounded like the feedback from her hearing aids, but the sound got more distant when I walked toward the hearing aid charger. It got louder as I approached the dresser, though. I moved around a few things on top, then opened a drawer, one that in my childhood my mom would have called a junk drawer. Back then, a junk drawer was a place to store pencils, loose change, batteries, and other things that tend to collect in a kitchen. Declining executive function supercharges junk drawers, collecting things that belong everywhere or nowhere. This one had empty candy wrappers, multiple toenail clippers, a fanny pack stuffed with incontinence products, part of an egg carton, paintbrushes, cardboard inserts from shoes, a bookmark folded up inside a coffee-stained napkin, a tiny segment of chain in a baggie, a container of chunky glitter glue, a 3x2” picture of me in high school, and so much more.

Unable to find the source of the sound, I gave up and went back upstairs so that at least I couldn’t hear what I couldn’t solve. Later, my husband looked. At one point, he moved the coffee cup on the dresser. Maybe he was trying to see what was behind it, maybe he was annoyed and acting it out by flailing, or maybe he tuned in to the dementia mindset. (He has been able to find things in the kitchen by saying, “if she were holding the cheese grater and was facing this direction, where would she put it?”) Whatever the reason, he found the source: As it turns out, coffee with a hearing aid at the bottom does make a remarkably loud screeching sound.

Is the material world inherently confusing or is it just confusing to me and for her? Pierre-Simon Laplace, an 18th century French mathematician, said this:

Given for one instant an intelligence which could comprehend all the forces by which nature is animated and the respective situation of the beings who compose it—an intelligence sufficiently vast to submit these data to analysis—it would embrace in the same formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the lightest atom; for it, nothing would be uncertain and the future, as the past, would be present to its eyes.

The intelligence he hypothesizes, later rebranded as Laplace’s demon, can deduce everything that has happened in the past and everything that will happen in the future. The demon is powerful enough to crunch all the data and smart enough to know all of science. It would know the hearing aid was screaming in the coffee. It would know when and how it happened. The demon could take some of the confusion out of the material world because it could know everything that happened. But I submit it could never take all the confusion out of the material world because it could not always know why things happen the way they happened.

Dementia defies Laplace’s demon repeatedly. Sometimes my mom will say something like, “Will you…” and then forget what she was trying to ask. What was the question she started to ask before losing the words? Maybe there was no question—maybe it was just a feeling. The feeling could have turned into a question, but the question is forever indeterminate.

Language might seem eternal, but it is bound to the passing of time. Julie Sedivy, scientist and polyglot, studies the relationship between language and time. She writes, “Language, in its everyday use, involves a frantic negotiation between future and past, though we ourselves are trapped in those pinhole moments between what has been uttered and what has yet to be spoken.” Usually, we don’t notice the pinhole because we are used to it, but speaking is incredibly complicated, and even a simple sentence requires memory. She explains:

You must form an utterance before you can speak it, but even as it forms in your mind, it rushes from future to past; its shape is already a memory even before you have opened your mouth. As best you can, you try to fix its image in memory as you prepare to speak it. But a full sentence in all its detail contains more information than your memory can easily hold, and if you wait until your sentence is completely formed in your imagination before you begin to utter its first syllable, it will have already begun to dissolve.

With dementia, you are forced to notice the pinhole. You have an idea for a sentence, an idea of an idea. You start to speak it before the idea is fully formed, but then the memory of what you were going to say is lost. “I need to say something about the dog,” you might think, but without even words yet. “The dog,” you say, but then you forget what idea you were forming. You don’t know what you were going to say, but you can tell that you are in that pinhole moment.

To know what my mom was intending to ask, Laplace’s demon would have to be a being that can transcend the dimensionality of time. Then again, if it knows from a position that transcends time, it would no longer be in the realm of human language or understanding, existing through time.

Dementia also leaves my mom in the presence of beliefs detached from the past. What turned my mom’s memory of our neighbor’s death by heart attack into a subjective certainty that he committed a family homicide and suicide? Why not, instead, a subjective certainty that he died of colon cancer, or that he is still regularly fishing on the lakes of Wisconsin? Don’t tell me that the reasons could be recreated by tracing the paths of all her neurons, or that they could be recreated by looking at all the data from her body and her environment.

I’m not saying that everything she does escapes the demon, but the reason she put the hearing aid in the coffee certainly does. A reason is bigger than a pinhole. Even in its omniscience, Laplace’s demon would have to give an explanation bigger than a pinhole. If the explanation is bigger than a pinhole, it doesn’t capture my mom’s experience. If the explanation is confined to the pinhole, it can’t be an explanation. She can’t be asked either—she herself likely didn’t know why.

The intermediate state between dying and being reborn is the most well-known bardo state, but there are others. This life is itself a bardo. Dying is a bardo. Falling asleep and dreaming are each bardos.

I like to think of those reasons not as existing in the demon’s causally deterministic world, but instead as existing in a bardo state. A bardo is an intermediate state between one life and the next and is the topic of the Tibetan Book of the Dead, also known as the Bardo Tödrol Chenmo. I learned a lesson about the bardo when my laptop entered one. I dropped a beautiful, illustrated copy of the Bardo Tödrol Chenmo on the screen, no joke. My laptop remained in a bardo state until it was reincarnated with a new screen. Sometimes the material world is blunt.

In his book about the Bardo Tödrol Chenmo, Sogyal Rinpoche says that the term bardo helps us see that life and death are inseparable “when seen and understood clearly from the perspective of enlightenment.” The intermediate state between dying and being reborn is the most well-known bardo state, but there are others. This life is itself a bardo. Dying is a bardo. Falling asleep and dreaming are each bardos. For Rinpoche, bardos occur when we see the potential for liberation emerging out of a period of uncertainty.

The quality of one’s consciousness is a central concern in Buddhism, which classifies our mental states into 52 kinds. Meditation, also, to simplify, is about becoming aware of one’s own mind. Rob Nairn interprets the Bardo Tödrol Chenmo in a book entitled Living, Dreaming, Dying. Speaking of the bardo at the moment of death, he says that most people stay unconscious at this point out of fear:

Fear is a big factor in the bardo, because we are going through massive changes. We experience the collapse of all the known and the familiar. The mind that we know in this world starts to disintegrate. The essence of what we've learned withdraws into a deeper level of our consciousness. This is why we experience our whole life as though it were a rerun and the essence is drawn out of it—the main themes of our habitual tendencies, whether positive, neutral, or negative. The mind that was involved with all those experiences disintegrates, collapses, and what we needed to hold ourselves in the world isn't there anymore; it dissolves.

I cannot find discussions of dementia as a bardo state in the Buddhist tradition. I don’t belong to that tradition, so I don’t want to make claims about the bardo, but I do find it helpful for myself to think of dementia as a bardo. Dementia also is a period marked by uncertainty, where the familiar collapses. It can be part of the process of dying. True, everything we do is something that we do on our way to dying, but dementia typically occurs late in life and involves the death of abilities: the ability to remember, to follow serial instructions, to plan, to prioritize, to finish a thought, to distinguish between reality and delusion. If falling asleep is a bardo, if dreaming is a bardo, then it makes sense for me to think that dementia is a bardo.

Bardos are states in which consciousness is revealed as consciousness. You understand that dreaming is a kind of conscious state because you wake up and vice versa. You understand that living involves many conscious states because you know that you were a child even though you remember nearly nothing. Dementia reveals the contingency of our minds, which is neither inherently and always good nor inherently and always bad. My mom gets frustrated by her inability to complete sentences or to find anything. She often feels stupid, and she fears further decline. Yet she also is not expected to cook or clean, to keep anyone alive, to tend to feelings, or to keep up appearances.

Shoes, medications, a tablet, and dust, have all at one time or another been the subject of delusions for my mom. If you have put away your shoes your whole life, why would you not be able to find them? Wouldn’t it make more sense that someone was hiding them? If you are feeling depressed, and you forget each day as it passes, wouldn’t it make more sense that your daughter is withholding your medications? Social media is a morass of photos with no apparent rationale. If you have chronicled your life in photo albums and now you are seeing neighbors you never really talked to, wouldn’t it make more sense that they are controlling your tablet? If your shelf has a dustless patch next to a knickknack, and you don’t remember moving it, wouldn’t it make more sense that your family is moving or stealing your possessions? Materiality is liminal and shoes are never just shoes.

Is she still herself in the throes of these delusions? At what point will she cease to be the same person? I have found that people reflexively find these questions to be important. I have had friends tell me that if they have dementia, they will no longer be themselves and therefore want themselves (that person?) to die. I have had friends tell me that if or when my mom is ever not herself anymore, I won’t have to feel bad if I stop taking care of my mom (this stranger?). A social worker told me that the lashing out at me is the Alzheimer’s disease, not my mom.

As long as she has the same moral conscience, she is still my mom, even if she forgets.

When is she herself? When isn’t she? If these questions are about whether she is acting in character, whether her behavior is normal, they are useful questions. If the questions are about identity, however, I don’t think they are useful questions. I’m probably in the minority in this belief. Many people have strong opinions about whether and how people maintain their identity. There’s a whole philosophical tradition exploring whether our identity is a function of our body, our mind, or our soul. Nina Strohminger and Shaun Nichols have tried to understand what people in everyday life think about what makes us the same person through change, philosophical arguments aside. They ask people about a fictional car accident victim who receives a brain transplant, varying how the brain transplant changes the victim. Then they ask whether the person is still the same person. In some scenarios, the victim is unable to recognize objects. In some, the victim becomes apathetic, losing all their desires. Strohmingher and Nichols find that the biggest threat is not loss of memory. The biggest threat is loss of moral conscience. Applying this to my mom, this would mean that as long as she has the same moral conscience, she is still my mom, even if she forgets.

Sometimes my mom acts out in her delusions by doing and saying things she never would have when I was a child. Back then, she would take turns waking up me and my siblings after all the others were asleep so she could spend one-on-one time with each of us. Her joy at teaching me to use a zipper, to read, to add, to tie my shoes, vibrated through me. Maybe I would have loved learning with a different mother, but my current love of learning is fused with her delight in seeing me grow. It’s not that she was never angry at me; the angriest I remember her being was when I was seventeen and stayed out late and didn’t tell her where I was. When she found me, she was so relieved, but also quite mad. “Get in the car right now,” she hissed. The anger made sense, so together, we could rebuild trust and navigate my increasing autonomy.

In her delusions, though, she can scream at me viciously in ways that defy all reason, including her own. She can’t say and doesn’t know why she is mad. I’m not a bad person, I tell her. I’m just trying to help. This woman who loves babies and art and values kindness and creativity has also trembled in anger, telling her granddaughter that she hates her and that she hopes she suffers. Maybe that will teach her a lesson, she tells me after spitting out her vitriol. I don’t ask what the lesson is. What lesson could anyone learn from having a finger pointed in their face and being told, “Fuck you, you fucking brat!”?

Imagine her giggling as she gets the middle fingers to stand up.

Yet my mom also can’t see a picture of a cute dog without wanting to show it to this grandchild. “She’ll love it,” my mom tells me. Speaking of the same granddaughter, she says, “Help me remember to show her when she gets home.” She is irreverent, poking the grandkids in the ribs and denying it, insisting that she didn’t feed the dog at the table by saying, “It wasn’t a full bite, just a crumb.”

When I was in high school, she helped chaperone the band trips, and I remember the adults still referring, years later, to those inside jokes she started. She taught our neighbor’s two-year-old to answer, “What does the kitty say?” with “Meow” and “What does daddy say?” with “More beer!” She also taught him to walk up to people and pinch their butts and say, “I goosed you!” My friends in high school on more than one occasion told me they envied my funny mom.

Now, she is still the life of the party—when we play Telestrations, a game that is a little like telephone, except you alternate between pictures and words, invariably she figures out that being kind of bad at the game makes it funnier and ends up making people laugh until their stomachs and cheeks hurt.

Her behavior during delusions is not normal for her. That makes a huge difference. Whether or not she is the same person as she was before she got Alzheimer’s disease makes no difference at all. She is in a bardo. Aside from interacting with my mom, I can usually make sense of the material world. That’s not because the world is inherently sensical. If I had a different mind, I would experience it differently. Shoes could be an easy part of my wardrobe that I normally put by the door but sometimes take to my room when I come home in a rush. Or shoes could instead appear without their history and take on new emotional meanings. They could be newly minted weapons in a war with my family.

I consider what Sogyal Rinpoche says about the bardo of dying, and think about whether it equally applies to dementia:

Perhaps the deepest reason we are afraid of death is because we do not know who we are. We believe in a personal, unique, and separate identity; but if we dare to examine it, we find that this identity depends entirely on an endless collection of things to prop it up: our name, our “biography,” our partners, family, home, job, friends, credit cards . . . We live under an assumed identity, in a neurotic fairy tale world with no more reality than the Mock Turtle in Alice in Wonderland. Hypnotized by the thrill of building, we have raised the houses of our lives on sand. This world can seem marvelously convincing until death collapses the illusion and evicts us from our hiding place.

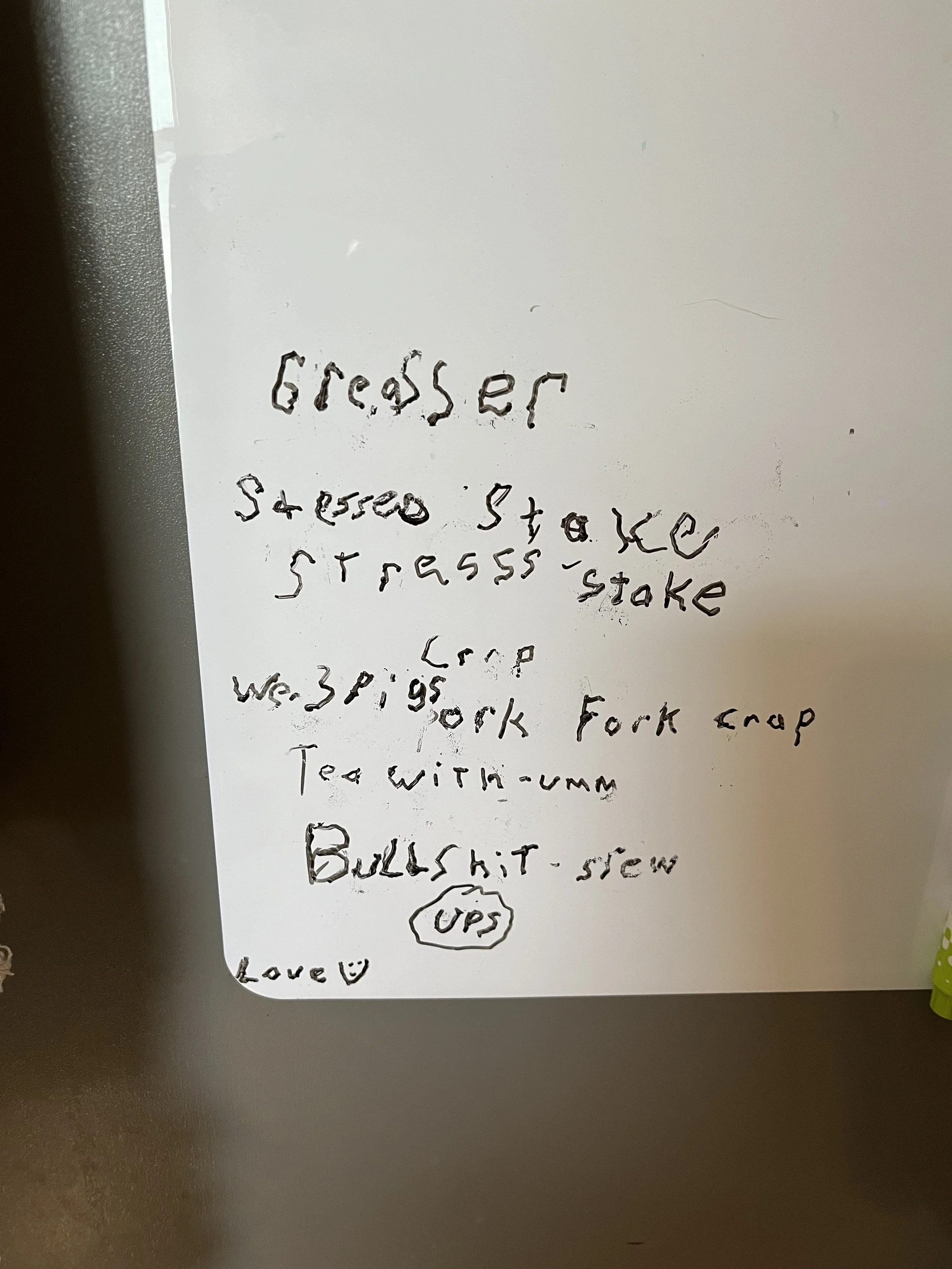

Here's our whiteboard where we write our meals. The “we 3 pigs pork fork crap” was a popular request.

Dementia collapses the illusion that the world makes inherent sense. It collapses the illusion that we have this unique and separate identity. We can become angry, suspicious, and paranoid. If I were to think that the question about her identity is the one that matters, I would be failing to see what dementia reveals. Dementia can cause the delusion that someone is hiding your shoes, but regular living can cause the illusion that my consciousness is stable, and the material world is fully known.

In dementia, the confusing nature of the material world comes from a loss of recognition. Fixating on the loss of recognition is a way of fixating on the question of identity and of avoiding recognition of dementia as a bardo. If we think that my mom needs to recognize me to care for me, that could be a mistake born of the fact that most people I interact with do not have dementia and do in fact recognize me as they care for me, and of the fact that I recognize the people I care for.

I don’t think my mom always recognizes me even though, so far, she does not forget my name, or at least she is still able to hide the forgetting if it happens, and she has never revealed that she has forgotten that I am her daughter. When she rages at me for stealing from her, she does not recognize me as me. I’m not a thief. I’m not abusive. If someone in pain came to me with a problem, I wouldn’t lie to them and trick them. That’s not in character for me.

The struggle and learning for me has involved how to keep recognizing her even through her profoundly uncharacteristic rage. But how can I say I recognize her if I don’t think that identity is what matters? Who am I recognizing?

The Milinda Panha is an ancient dialogue between the Bactrian King Meander (Milinda) and the Buddhist monk Nāgasena. Through questioning, Milinda prompts Nāgasena to explain various Buddhist doctrines, including the doctrine of anatman, or no self. We have no persistent soul or anything else that would make us persist through time: not memory, not the body, and not the “moral conscience” that Strohminger and Nichols say that we hold onto either:

“He who is reborn, Nāgasena, is he the same person or another?”

“Neither the same nor another.”

“Give me an illustration.”

“In the case of a pot of milk that turns first to curds, then to butter, then to ghee; it would not be right to say that the ghee, butter and curds were the same as the

milk but they have come from that, so neither would it be right to say that they are something else.”

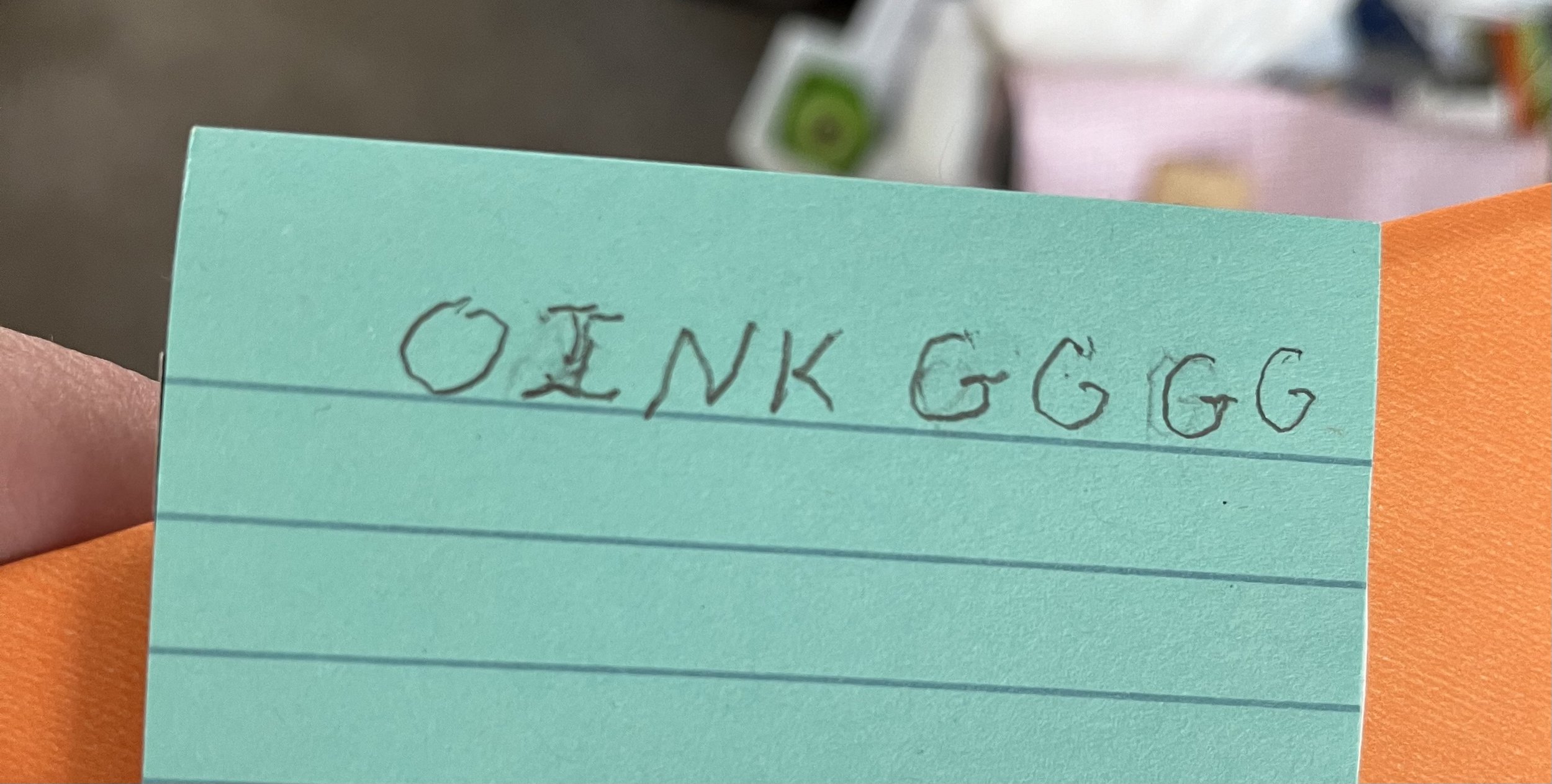

Notes like this appear regularly in bizarre places.

This conversation is about rebirth, but it equally applies to different stages of life. I am not the same person as the infant born many years ago, but I am not someone else either. I have come from that newborn. Thus, Nāgasena would reject the question of whether my mom in her delusions is identical to the mom who taught me to hold a kitten gently. The mom I take care of came from the mom who took care of me. She is not the same person, but she is not someone else either. This one came from that one: that’s what matters. Knowing this keep me going. It helps me hang on to the “that mom.”

One day, I found a note that my mom had written, one written by a mom who had come from a mom who was an irreverent, life-of-the-party mom.

Even though I don’t exactly know what the joke is, I know she wrote that to make someone laugh when they found it. That alone made me smile. Even without identity, the ghee (the silly GGGG?) still comes from the milk. My mom’s note helps me remember to let go of knowing the reasons why she does what she does. Why OINK GGGG instead of OINK HHHH or OINK GGGGGGG?

The world is not a vessel of sensical entities. Her note helps me remember that she is living in a bardo, and so am I. Her note also helps me remember that whether she is the same person as the one who raised me is less important than whether she came from the one who raised me. She is.

Chris Weigel is a professor of philosophy at Utah Valley University, where she has been teaching for over 20 years. She received her bachelor’s degrees in music performance and philosophy from Lawrence University and her Ph.D. in philosophy from Temple University. She has published academic papers on confabulation, free will, and most recently, on the ethics of caregiving for people with dementia. She lives in Salt Lake City with her family and her mom, whom she has been taking care of since 2018.