“Hear me, hear me, ye who are alive!”

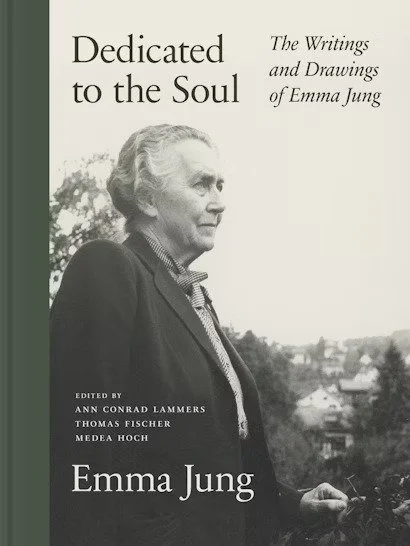

A review of Dedicated to the Soul: The Writings and Drawings of Emma Jung, edited by Ann Conrad Lammers, Thomas Fischer, and Medea Hoch, translated by Ann Conrad Lammers and Alison Kappes (Princeton University Press, 2025)

by Susan Rowland

432 pp., hardcover, $45

Jan. 14, 2025

Princeton University Press

ISBN: 9780691253275

Emma Rauschenbach Jung (1882-1955) has been too often overlooked as a significant collaborator with her husband, Carl Gustav (C. G.) Jung. Dedicated to the Soul, a welcome volume of mostly unpublished material, features her lectures, poems, a verse play, and records of dreams, together with invaluable introductory essays and notes by Jung scholars. The inclusion of Emma’s paintings, notebooks, and sketches substantiates her role as an important contributor to Jungian psychology in full color. All is superbly translated into English and joins her previously available works, Animus and Anima and The Grail Legend (completed by Marie-Louise Von Franz), to establish Emma Jung not only as a pioneer of analytical psychology but also a soulful artist in her own right.

C. G. wrote prolifically on his theories of the Unconscious, the storehouse of collective “archetypes” or patterns of creative energy shared among human beings. The fine biographical essays in Dedicated to the Soul illustrate how Emma aspired not only to support her husband’s work, but also to make significant contributions to it. One thing that strikes the reader of this volume is that Emma’s imaginative output echoes, complements, and illuminates that of C. G.’s, whom she married in 1903. For example, some of her paintings resemble themes in The Red Book, his vividly illuminated folio produced between 1913 and 1930 and first reproduced in 2009. The humor of her verse play “Mystery of the Crusade” (1926) deserves to be read alongside C. G.’s much later Answer to Job (1952). Emma’s dreams that appear in C. G.’s multivolume Collected Works without named attribution are here given a fuller context, and her poem, “Sermo ad vivos” (1920), we are told in a footnote, probably refers to C. G.’s Septem Sermones ad Mortuos, privately published in 1916. The opening of the poem seems to resonate with the contrasting ethos of Emma Jung:

I heard a voice crying through the night:

Hear me, hear me, ye who are alive!

Open your ears to my word

Whereas C. G. seeks to command those in what might be called a purgatorial territory in Septem Sermones, Emma’s poem addresses the lifelong task of every person to individuate or to develop a spiritual life. The poem exalts the living while Septem Sermones scolds the dead for their failure to do so.

Emma Jung’s focus on living a psychologically developed life unites the material of this volume. Although some early poems, such as “Grief” (“Trauer,” November 1917), suggest a period of anguish that is easy to attribute to tensions in the Jung marriage, Emma sees a bigger purpose in the dialogue verse, “A Death is Come Upon Me” (“Es ist ein Tod gekommen über mich,” January 1918). After some terrible loss, the poet is estranged from her life. A voice tells her to listen to the “God of Truth.” Then another says that only beauty can be relied upon. A third declares:

Illusion, all illusion!

Truth is a true illusion,

beauty a beautiful illusion,

yet illusion it all remains;

and without human beings, not even that.Therefore:

Real and of meaning is only

the human being and the human soul.

The poem’s connection of the soul to meaning recalls Emma’s often-overlooked contribution to analytical psychology: her recuperation of the animus. While C. G.’s work displays little patience with this masculine aspect of a woman’s psyche, Emma’s essay, “On the Nature of the Animus” (“Ein Beitrag zum Problem des Animus”), presented to the Analytical Psychology Club in 1931, offers the animus as a woman’s initiation into power, deed, word, and meaning. (Personally, I am sorry that Dedicated to the Soul does not include the animus essay, which deserves to be much better known, and can be found alongside her insightful essay on the anima in Animus and Anima). Her potent depiction of the animus contrasts with C. G.’s fixation on women trying to access power through this masculine side in order to over-hasten individuation. The fatal result, he claims, is an overly opinionated woman. For Emma, however, the animus provides a soul-making journey for women, leading to a spirituality of numinous meaningfulness. Hence Emma, a lifelong member of the Swiss Protestant Church, finds security in religion as a psychological home without being stuck in doctrine. Her animus is rendered into a reliable guide to individuated being or life in the soul.

A look inside Dedicated to the Soul. Courtesy of Princeton University Press.

In Emma’s artful expressions of her animus, he appears to her as a visionary character, Aranû. She sees him “stepping out of the black sky—his head a red, blazing star, and in his right hand a flaming sword.” Is there somewhere in the Jung archives another Red Book, this time authored by Emma Jung? Appearing in texts collected in the chapter “Dreams and Fantasies,” Aranû is not unlike C. G.’s Izdubar in acknowledging he is given life by the psyche of the dreamer, and he is also a cousin to C. G.’s Philemon in providing teaching from the God who creates. Crucially, Aranû is complex and a complex; as masculine fire, he is part of Emma’s soul, a fragment of what Emma has no hesitation in identifying as the divine. Her frequent references to this inner divinity as “the soul,” the Greek word psyche still at the heart of psychology, differs from C. G.’s perhaps more clinical term for such archetypal comprehensiveness, “the self.”

Around the time of the arrival of Aranû in 1916, Emma began work on what she came to call “the System,” her own cosmology weaving together astrology, the Grail legend, and dreams. Crucial to “the System,” the subject of the final chapter of Dedicated to the Soul, is its origins in Emma’s inner life, presenting currents of her individuation in the form of a planetary design in a cosmos that unites inner and outer meaning. Emma’s drawings and notes provided in Dedicated to the Soul show a concern with fundamentals of creation, together with questions of order and chaos. This volume also supplies Emma’s 1919 painting “Image of an Emerging World,” which contains many of her cosmological symbols and referents. There is exciting research to be done on Emma’s cosmology and its referents in analytical psychology.

In my opinion, every woman has an element within herself… something natural, free-roaming, something that desires to be unrelated—to be sufficient unto itself.

The book’s opening biographical essays by Susanne Eggenberger-Jung, Thomas Fischer and Medea Hoch, and Ann Conrad Lammers give the context of Emma’s life, including her already widely known devotion to her family. Perhaps she herself would have presented this book as an adjunct to C. G.’s work. For such a conception of Emma Jung, we have the evidence of her letters, which show her as an active correspondent in the growing field of analytical psychology. Indeed, the volume bears witness to her lifelong devotion to her husband’s work, but her letter to fellow psychologist Erich Neumann from 31 March 1950 has this remarkable comment:

In my opinion, every woman has an element within herself that one could perhaps call the Artemis component: something natural, free-roaming, something that desires to be unrelated—to be sufficient unto itself, something that wishes to be neither daughter, nor wife, nor mother. Mostly it is very hidden and unconscious, because consciously, women are most often completely tuned in to relationship. . .

Ultimately, Dedicated to the Soul is a testament to this little known “Artemis component” of Emma Jung, offering readers an encounter with the ways Emma manifested her most precious soul. Not possible to document here are her many decades as a Jungian analyst and teacher of analysts, let alone her founding work in the Analytical Psychology Club. Yet Emma Jung was complex. She found a way through the painful complications of her marriage to an independence of soul. Nothing about that independence took her away from her devoted love for husband, children, and family.

No doubt Emma Jung would have vigorously rejected any suggestion of feminism on her part. And this review is not the place to rehearse the multiple and contradictory directions of that enterprise. While I hope this book is the start of re-evaluating her contribution to analytical psychology, her work is multifaceted, transdisciplinary and soul-making. In rescuing woman’s soul from C. G. Jung’s jaundiced account of the animus and embodying an enlivening spiritual independence, Emma Jung is certainly a role model.

Susan Rowland, PhD, teaches at Pacifica Graduate Institute and is the author of ten books on Jung, the feminine, and the arts including Jung: A Feminist Revision (Polity, 2002) and Jungian Literary Criticism: The Essential Guide (Routledge, 2019). Susan’s novels, most recently Murder on Family Grounds (Chiron Publications, 2024), featuring a triple goddess detective of marginalized women, explore feminine heroism as a way to cultural renewal.