To See Beyond Walls

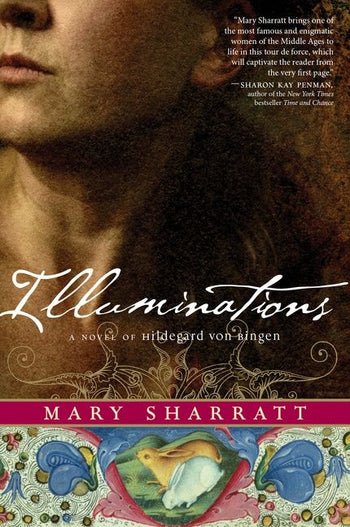

A Review of Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen by Mary Sharratt

By Cheryl Sadowski

Mother knelt before me so that our faces were level.

Her hazel eyes seemed as huge as the orbs that swam across my vision.

“You are the tenth child,” Mother said again.

I was the tithe.

288 pp., paperback, $15.99

October 2013

Mariner Books

ISBN: 978-0544106536

With these chilling words, the fate of eight-year-old Hildegard von Bingen is quite literally sealed.

It is 1106 in the Rhineland valley, western Germany. Hildegarde’s father and older brothers are fighting in the Crusades. Hildegard’s mother is busy paying fealty to the von Sponheims, a wealthy German family of noble descent. The Sponheims’ daughter, Jutta, is six years older than Hildegard. Beautiful and at a marriageable age, Jutta is plagued by shame and anger. She channels her damaged spirit into an obsessive fascination with purity and devotion, deciding to live the most extreme version of holy life as an ascetic according to the Rule of Saint Benedict.

Because she is a noblewoman, Jutta requires a companion. Conveniently, it is little Hildegard, who is haunted by visions of orbs and light that cast her as both blessed and cursed. Troubled by Hildegard’s visions and eccentricities, her mother gives her up as an oblate to Jutta and the Church. Jutta and Hildegard become anchorites, living out their lives walled in to two rooms, each no longer than five paces, which adjoin the church of Disibodenberg monastery. Their only portal to the world is a screened window through which they observe Mass and a revolving hatch through which frugal meals are delivered by anonymous monks.

What sounds like it could be the plot of a horror film was part of ordinary life in medieval times when women mostly, but also some men, chose to live in poverty and prayer, bricked within an anchorage—a word derived from the Greek verb, anachoreo, “to withdraw.” Such sacrifice was not always freely given. Parents were known to offer their offspring to the Church, where it was reasonably assumed they would be cared for in exchange for service later in life as nuns or monks.

For women in particular, living in a religious order was an opportunity to trade child marriage, sexual violence, and perpetual pregnancy for a life of contemplation, music, and artistry. Though they were confined, women received regular sustenance and were educated in Latin, Scripture, theology, philosophy, and medicine. They wove tapestries, sewed banners, composed music, and illustrated manuscripts. Some, like Jutta and Hildegard, became wildly popular, sought by pilgrims and nobility who traveled long distances to hear their words and make donations to the monastery in which they were held

Though they are walled in together, Hildegard injects expansiveness and creativity into the young oblates’ lives by cultivating their innate talents in song and study, helping them make the most of their living entombment.

In Illuminations, Mary Sharratt embroiders Hildegard’s story with all the detail and color of a medieval tapestry. As Jutta and Hildegard grow up inside their anchorage, Jutta falls ever deeper into her macabre, self-imposed “sepulcher of deprivation.” When the Margravine von Stade arrives to give two nieces in oblation to Jutta, Hildegard implores her to think otherwise. The margravine is affronted by her impertinence and remains stalwart in her decision, but she takes notice of Hildegard’s compassion, intelligence, and bravery.

Years pass, and Hildegard protects the girls from Jutta’s tyranny and increasingly morbid devotional practices. Nuance and intrigue characterize daily battles of will between the two women. Though they are walled in together, Hildegard injects expansiveness and creativity into the young oblates’ lives by cultivating their innate talents in song and study, helping them make the most of their living entombment.

After Jutta dies, Hildegard becomes Magistra of Disibodenberg, and her life changes dramatically. The Margravine von Stade appears once again, this time with her own daughter, Richardis, a silent, troubled beauty who chooses the limited freedoms of cloistered life over the limitations of a noble marriage. Hildegarde accepts Richardis as her oblate, bestowing enormous riches upon Disibodenberg, an arrangement the margravine cleverly leverages to enable the women and girls to move freely about the abbey, as the monks do.

Hildegard nurtures, mentors, and loves Richardis. Richardis encourages Hildegard, now in her forties, to begin recording the visions she has kept to herself for so long. Her autobiographical work, the Liber Scivias, or Know the Ways, draws grave attention from the male-dominated Church for its characterization of God in distinctly feminine and panentheistic terms: she refers to “the living light” as Ecclesia, “my God, Mother of the true Church,” “the towering woman,” “divine love abiding within in all living things.”

Hildegard’s narrative is vested with such authentic interiority and feeling that it’s impossible to not root for her success at every turn.

Hildegard’s reputation gradually extends beyond the abbey walls, and she grows in confidence and influence. Compelled by her visions, she seeks to establish her own religious order outside Disibodenberg, creating a power struggle with Church patriarchy that requires deft dealings with the Archbishop Adalbert; Bernard of Clairvaux, the pope’s advisor; and eventually, Pope Eugene III himself.

Sharratt never overlooks Hildegard’s own failings: in her quest to establish a new cloister, she is riddled with pride and anger when some followers abandon her for another order. Hildegard’s narrative is vested with such authentic interiority and feeling that it’s impossible to not root for her success at every turn. Cleaving to faith in her visions, she evolves from oblate to mentor, from troubled visionary to polymath, prophet, abbess, and Sybil of the Rhine.

Author Mary Sharratt has lived in Europe for more than 20 years and written about some of the most fascinating women from medieval and Renaissance history. Subjects from other novels include Christian mystics Margery Kempe and Julian of Norwich; composer and artist Alma Schindler Mahler; poet Aemilia Bassano Lanier; and the Pendle Witches, who had reputations as cunning women and healers.

In Illuminations, Sharratt takes some liberty with history: records suggest Hildegard more likely entered the anchorage at age fourteen, and her true feelings about Abbess Jutta and Abbott Volmar are unknown. But these shadowed corners have no impact on the bright light Sharratt casts upon one of Christianity’s most enigmatic female mystics. Hildegard’s fusion of a feminine God with the ever-unfolding harmony of nature set her apart from traditional Catholic dogma and place her in a pantheon of her own creation.

Cheryl Sadowski writes essays, reviews, and short fiction. Her writing explores the plain weave of everyday life with literature, art, and the natural world. Cheryl’s lyric poem “Tenants” was awarded a first place Grantchester Prize by The Orchards Poetry Journal. Other works have appeared in About Place Journal, EcoTheo, After the Art, and Bay to Ocean Journal. Cheryl lives in Northern Virginia, where she works as a communications consultant. She recently completed her Master of Liberal Arts degree at Johns Hopkins University.