“Spirit in the Dark” Brings Religious Influence to Light

by Mary Amendolia Gardner

Out of a dark place in American life, came beautiful people whose lives continually intersected with the broad American contemporary culture, with enduring effects.

A new exhibit, Spirit in the Dark: Religion in Black Music, Activism and Popular Culture, at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, examines Black religious life through photographs and several carefully curated pieces of material culture from the vast collection of the Johnson Publishing Company, publishers of Ebony, Jet, and Negro Digest.

The description of the exhibit rightly describes religion as “essential to the story of Black America.” The title borrows from Aretha Franklin’s 1970 song, “Spirit in the Dark,” and the photographs on display represent a very small fraction of the massive collection — over 4 million photos and negatives including 10,000 audiovisual items — now owned by a consortium including the NMAAHC, the Getty Research Institute, and several private foundations.

Three sections lead the viewer through the exhibit: Blurred Lines: Holy Profane, Bearing Witness: Protest Praise, and Lived Realities: Suffering and Hope. Each section highlights well-known Black American leaders and their cultural contributions, whether as an advocate, writer, or musician, virtually all people of faith. The plurality of religious expression represented by the figures ranges from Buddhism, Bahá’í, various forms of Christianity, Islam, and for at least one person in this exhibit, no religious affiliation. This exhibit invites the viewer to linger, listen, and learn.

The invitation to listen is two-fold: to the stories the exhibition tells about the subjects, and to the music that hums along in the background. The curators helpfully compiled a diverse and lively playlist to accompany this exhibition: four and half hours of music on Apple Music, YouTube Music, and Tidal, everything from Stevie Wonder’s “Higher Ground,” to Fannie Lou Hamer’s “Woke up this Morning,” and even John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme, Part 1”.

At first glance, an exhibit composed of celebrity images feels less than substantive, an exhibit more about the people themselves than faith or the influence they may have had on the faith of others. And yet these famous faces shaped, formed, and informed American culture in significant ways.

Photographs can of course stand alone as art, but the curatorial decision to set the photos in this context and not also in their original form in the magazine is an interesting choice. What stories originally accompanied these photographs? Did the stories discuss the celebrities’ faith? A digital age, in which users swipe to the next photo in seconds, may be less accustomed to the tangible action of tearing out a page from a magazine to keep and save, but understanding how the original readers experienced the photographs and the medium for which the photographers worked would have added additional context.

Equally, the art of magazine design — of which Johnson Publishing was an exemplar — relies on the ability to place stories in context -- not merely the context of advertising (a commonality with today’s digital presentation of images) but also of the relation of one story to the next. Something of that art could have been presented here had the curators chosen to show not only the photographs but their placement in the weekly magazine. The room in which the exhibit is displayed is cavernous -- one has the sense the space could have been more fulsomely used. Or perhaps that is precisely the point: out of a dark place in American life, came beautiful people whose lives continually intersected with the broad American contemporary culture, with enduring effects. What would jazz be without Dizzy Gillespie, literature without Toni Morrison, or the civil rights movement without Mary Church Terrell.

In Montgomery, AL, 1965, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King lead a group of protesters during the Selma to Montgomery March. Photo by Moneta Sleet Jr. (1926–1996). Johnson Publishing Company Archive. Courtesy J. Paul Getty Trust and Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Still, the photographs are superb, including the work of such renowned photographers as Norman L. Hunter (art director and award-winning artist), Maurice Sorrell (the first Black member of the White House Photographers Association), Moneta Sleet Jr. (widely respected photographer of the civil rights movement), D. Michael Cheers (Fulbright scholar, award-winning photojournalist, and documentary filmmaker), and others. Too frequently, the names of these artists are not well known or are forgotten, ironically, in a culture that gives such weight to celebrity. Kudos to the NMAAHC for highlighting their art and work, as well as the lives they documented.

This exhibit bears witness well to specific points in history, including the history of the struggle against segregation and the triumphs of the civil rights movement during the heyday of the publications through to the 1980s. These photographs document both the struggle and the beauty of artistic expression. This exhibit lends itself to ongoing conversations about the nature of the artistic calling and about these artists’ place in the broader American story, equally so for the photographers and their famous subjects. It is easy to imagine older museum-goers reflecting on these photographs and perhaps even recalling, in the distant chords of memory, seeing them for the first time in the magazine itself -- another reason to have expanded the exhibit’s scope.

This exhibit is not afraid to discuss religion, art, and politics; in fact, it invites further exploration of those topics as they relate to the artists’ lives. How did those artists live out their faith? Is their faith a part of their legacy, how they are remembered today, or are viewers surprised to see faith associated with their names? For example, the exhibit label for Prince cites that “friends described him as ‛very religious’ and yet his lyrics were “some of the most sexually explosive.” It is interesting that a museum can spark this kind of reflection and possible conversation, whereas it is a sad commentary on some religious institutions’ inability to have courageous conversations on these subjects. Perhaps religious communities might take inspiration from this exhibit and engage helpfully in dialogue with both their adherents and those on the outside.

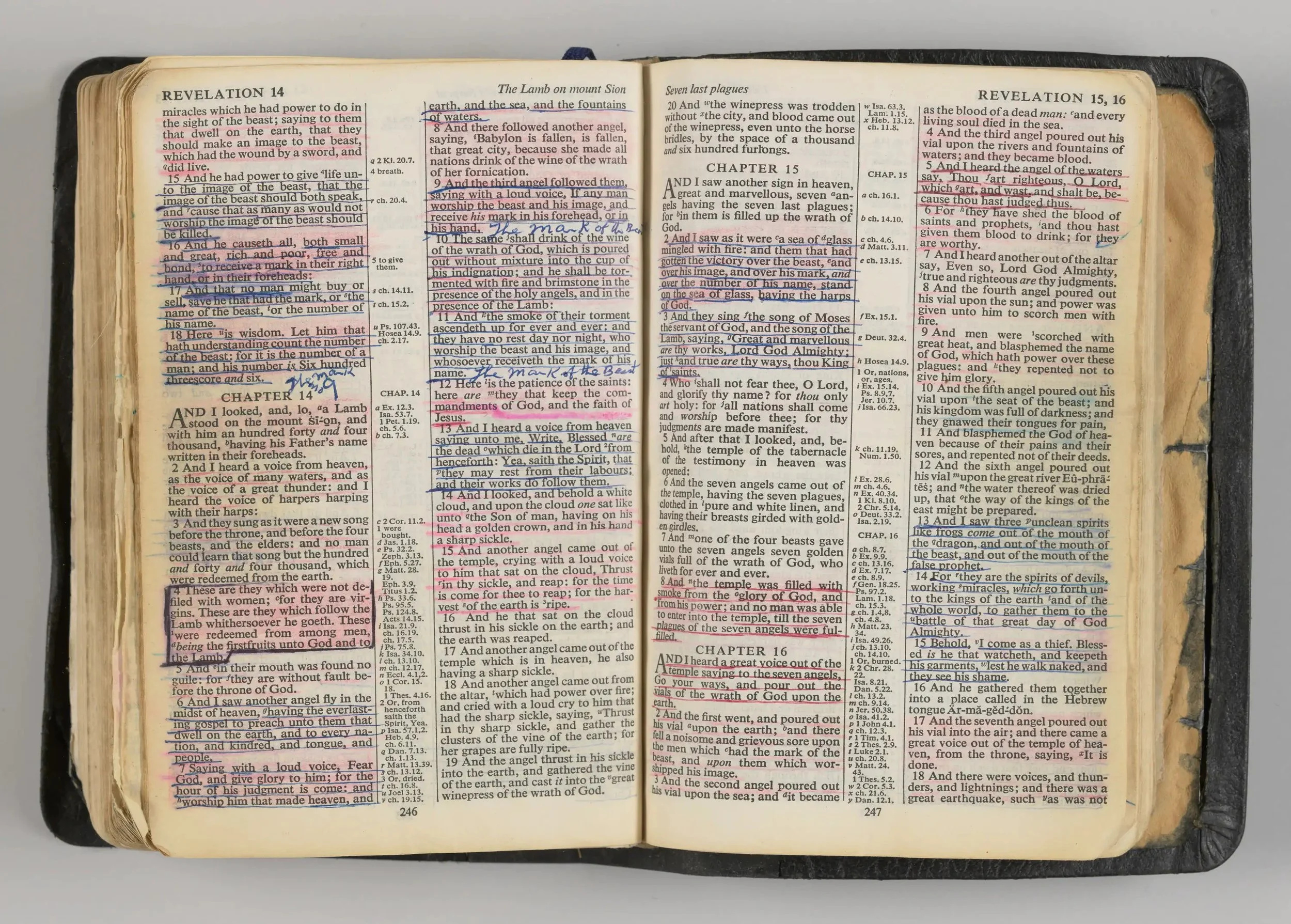

Little Richard’s Holy Bible, King James Version, ca. 1959. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

In 1975, Johnson wrote a “Publisher’s Statement” on the magazine’s anniversary, declaring that “Ebony was founded to provide positive images for Blacks in a world of negative images and non-images. It was founded to project all dimensions of the Black personality in a world saturated with stereotypes.” “Positive images” may be seen as having two distinct meanings: the one Johnson intended of providing a counterweight to a culture that downplayed and ignored the many contributions of Blacks to American life; and its artistic meaning in photography of the image displayed to the public, rather than the negative used in developing the image. In an age of TikTok, Instagram, and other social media platforms it is worthwhile from time to time to slow the pace of our visual consumption and spend time with photographs, which mark a specific period of time and capture a single moment within that time.

The selection of material culture adds richness to the exhibit. Notice the chapter of the Bible open on Little Richard’s well-worn, tattered, and much underlined Bible or the handwritten notes of James Baldwin on hotel stationery. Other objects shown help the viewer understand the people depicted.

As I listen to the playlist, my mind goes back to that cavernous room, remembering the dedication and work of the famous writers, artists, sports figures, and advocates. It is good that NMAAHC has collected, displayed, and given space to these familiar faces so that the viewer may learn about the faith that inspired their work.

Spirit in the Dark: Religion in Black Music, Activism and Popular Culture is on view at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture through November 2023. The exhibit is presented by the Museum’s Center for the Study of African American Religious Life and the Earl W. and Amanda Stafford Center for African American Media Arts. A companion searchable digital exhibit is also available through the Searchable Museum website.

The Rev. Dr. Mary Amendolia Gardner is an Anglican priest and Spiritual Director with Coracle. She recently completed her DMin. in Curating Community through the Arts at Wesley Theological Seminary and is also a practicing artist.