Three Days and Three Nights

by Douglas Porter

As an artist, I do not think about myself as a creator. I prefer to think of myself as a maker. A creator brings into being something that did not exist before. A maker pulls together materials along with ideas and concepts from the already-existing world of human culture and history, and forms them into some kind of entity. The particular configuration of elements that comprise the artwork may not have existed before — in that sense it is indeed “new” — but not “created.”

Even the designation “maker” can suggest that the artist is the primary agent in the process of art-making. My experience is that there is an undervalued aspect of passivity in the role of the artist. The artist needs to repeatedly “listen to” the artwork itself throughout a process that is essentially dialogic.

I take continuing inspiration from this quote in Christian Wiman’s Zero At The Bone: “Why is life sacred? Because we experience it within ourselves as something we have neither posited or willed, as something that passes through us without ourselves as its cause — we be and do anything whatsoever because we are carried by it.” This resonates with me when I encounter one of my paintings made years earlier. My recurring response is, “Where did this painting come from? I have no idea!” The painting did not originate with me — but it somehow passed through me.

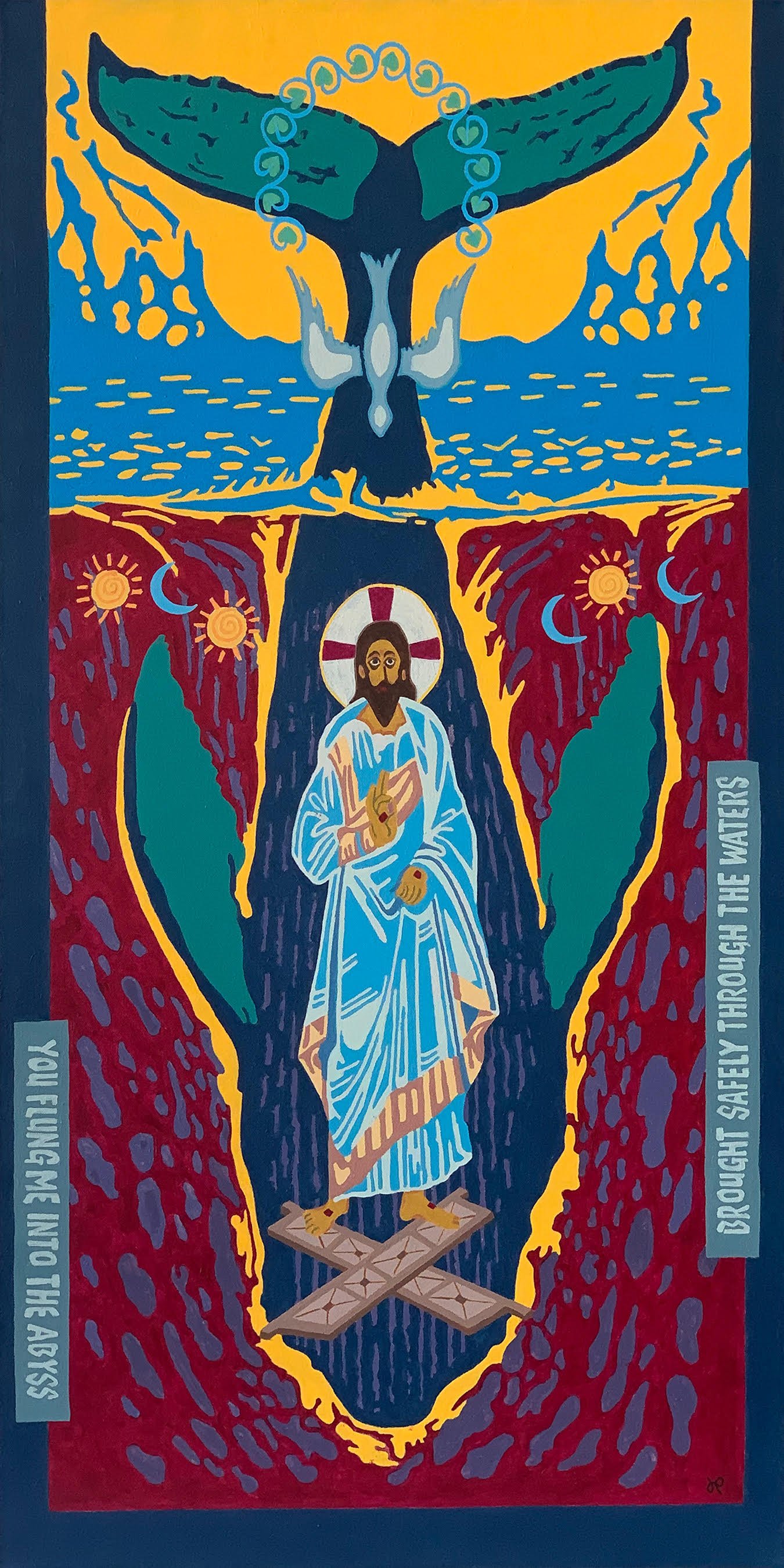

Three Days and Three Nights, 2022. Acrylic on canvas. 48 x 24 inches.

What I like a painting to do is suggest associations between images and ideas that are not common or familiar, but are often embedded more deeply in our culture. They are the very real undergirding of our culture. In Three Days and Three Nights, the figure of Jesus is placed inside the belly of Jonah’s whale. This is a visual working of the section of Christian scripture, where Jesus says: “As Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of a huge fish, so the Son of Man will be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.” Several Christian traditions have interpreted this as Jesus speaking of the three days between his death and resurrection, when he would descend into hell to “preach to the spirits in prison” (1 Peter 3:18). So the figure of Jesus is here placed in the whale descending into the depths. And at Jesus’ feet are the gates of Hell [traditionally depicted in the formation of a cross] that he has broken down.

Other elements in the painting are also pulled from various traditions: The roiling blue waters, at the top of the painting, suggest the waters out of which God formed the ground to be the habitation of all life. The text “You flung me into the abyss“ is a quote from Jonah 2:3 that Jonah spoke from the belly of the whale. The dove of the Holy Spirit references the Spirit of God that hovered over the depths at Creation and the dove that was present at Jesus’ rising out of the waters at his baptism. It may also not be coincidental that Jonah is the Hebrew word for “dove.”

John The Messenger, 2022. Acrylic on canvas, 40 x 30 inches.

John The Messenger is another example of my approach to painting. The central figure is John the Baptist from the Bible. The various elements assembled in this painting suggest that John had affinities with another biblical figure, that of Moses. Both men (1) were recognized as prophets; (2) led their people through wilderness and water to return them to God; and (3) announced the coming of the Chosen One (the Messiah). I also presented John with wings, as he has often been depicted this way within the Eastern Orthodox tradition because he was perceived as a messenger from God, angelos, an angel.

Most of my paintings involve a re-working of traditional Christian imagery. For quite a while the secular world has received this imagery as “devotional” and hence not to be taken seriously. My interest is in re-presenting this imagery in a more narrative context that also facilitates some kind of spiritual wisdom or insight. This strategy also has the secondary hope that my paintings will suggest that the plethora of images flooding our daily consciousness are “devotional” toward a range of gods of our own making.

In the end, I like to think of the artwork as gift. It is a gift to me because the process of art-making is always an invitation to reflect, explore, play, to ‘“break open” the common and familiar. And hopefully it is a gift for viewers, encouraging them to take the time to do the same. There is a chance this will disrupt or confuse. But this too may be a gift.

Douglas Porter is a visual artist whose video art has been shown in festivals and galleries in Canada, the United States, and throughout Europe. His recent art practice has moved into acrylic on canvas in an attempt to explore what contemporary devotional images would look like. He also develops visuals for worship spaces using different media. Doug currently resides in Orillia, Ontario, Canada.