The Din of Iniquity

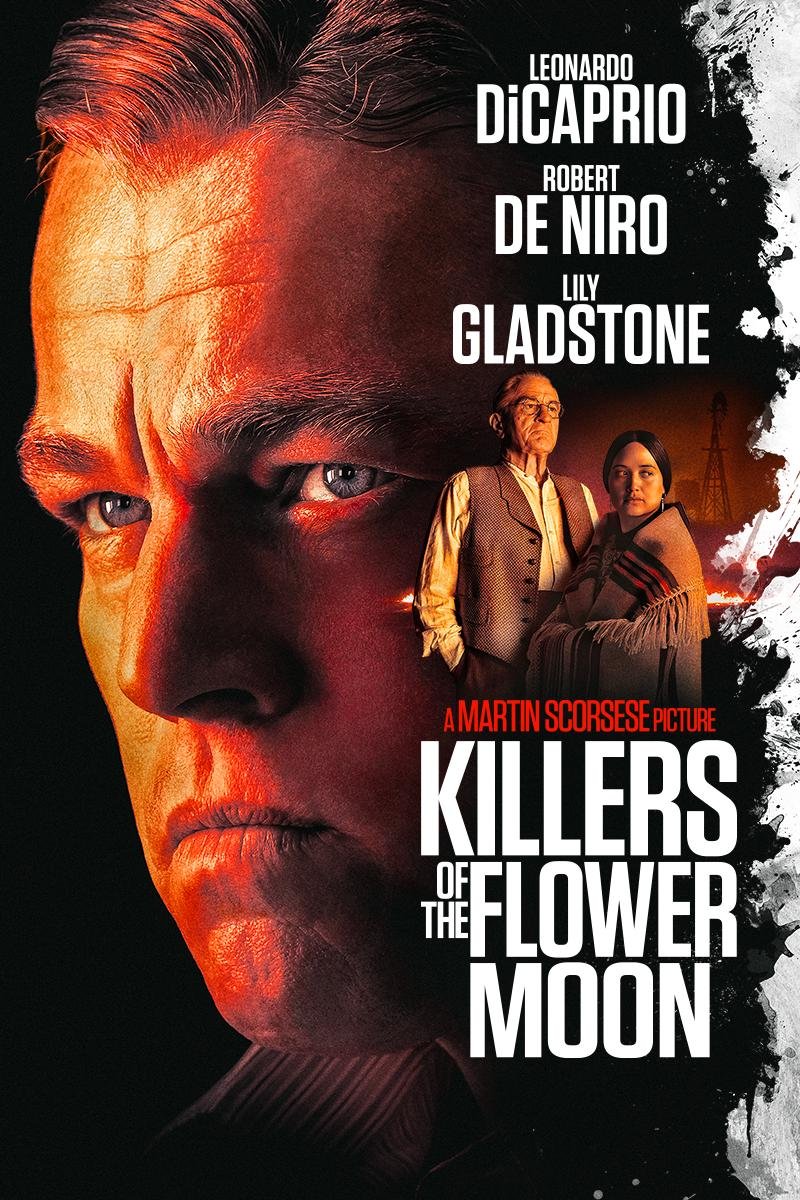

A review of the film Killers of the Flower Moon by Martin Scorsese

by John Kendall Hawkins

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Based on the book of the same name by David Grann

Paramount Pictures, 2023

Drama | R | 3h 26m

Killers of the Flower Moon was nominated for 10 Oscars this year but won none. As with many films by Martin Scorsese, it’s long, presenting in just under three and a half hours. This exposition provides ample time to get immersed in the story by way of character arc and how each of the protagonists responds to the tension built by the steps of the plot. Most of Scorsese’s epic films involve confrontation and violence, gangs, cabals and criminal families, and often a heaping helping of psychopathology. One thinks immediately of Taxi Driver (1976), Cape Fear (1991), and even The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), but there are many others over his long, enthralling career.

Killers of the Flower Moon can be seen as a crime thriller. The IMDB storyline is simple and a good place to start an analysis of the narrative and characterization: “When oil is discovered in 1920s Oklahoma under Osage Nation land, the Osage people are murdered one by one — until the FBI steps in to unravel the mystery.” This is sufficient, but it is not a full account. Having read the book (2017) by David Grann, which bears the subtitle The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, for instance, I know that Tom White, the FBI agent played by Jesse Plemons, was a star of the book and that the FBI tale took up two-thirds of Grann’s narrative. Tom White is an imposing ex-Texas Ranger, but Plemons’s White quietly blows into the “boomtown” — albeit in keeping with the character of the FBI at that time, which had no arrest powers and carried no weapons — and he doesn’t arrive until about two-thirds of the way through. Plemons is not the star. The big roles go to Robert De Niro (William Hale), Leonardo DiCaprio (Ernest Burkhart), and newcomer and Native American actress Lily Gladstone (Mollie Burkhart).

The film begins with a 1920 black-and-white newsreel backgrounder about the Osage and their discovery of oil and the curious observation about their wealth, relative to the world: “The world’s richest people per capita.” The film ends with a tribal ceremony or dance, when the Osage dance around a circle of drummers and form what appears to be a flower, which reminds one of Grann’s description in the book: “tiny flowers spread over the blackjack hills and vast prairies in the Osage territory of Oklahoma. There are Johnny-jump-ups and spring beauties and little bluets.” And then oil and evil men arrive and choke it all with, as Grann puts it, “spiderworts and black-eyed Susans, [which] begin to creep over the tinier blooms, stealing their light and water.” Thus, the wealth created by the dinosaurs (fossil fuel) is contrasted with the simplicity and presumed integrity of the tribal milieu.

What’s missing is a sense of who the Osage are. There is something generic about the Scorsese depiction, in contrast to, say, the care to establish rituals that director Kevin Costner takes with Dances With Wolves (1990). Such missing information might have been partially filled in by replacing the beginning and ending of the film — especially the oddly-placed end stage show depicting the Osage murders that includes Scorsese himself standing up at the microphone and delivering pap — with historical information.

The Osage Nation (the name is an English rendering of the French phonetic version of Wa-zha-zhe), comfortably ensconced in Missouri, was one of the many Native American nations pushed out by white Western expansion. Grann writes in his book that “the Osage were forced to cede nearly a hundred million acres of their ancestral land, ultimately finding refuge in a 50-by-125-mile area in southeastern Kansas.” Ouch. Then they were promised by Thomas Jefferson that they would not have to move again. But he lied. As Grann writes,

The Osage had been assured by the U.S. government that their Kansas territory would remain their home forever, but before long they were under siege from settlers… In 1870, the Osage—expelled from their lodges, their graves plundered—agreed to sell their Kansas lands to settlers for $1.25 an acre. Nevertheless, impatient settlers massacred several of the Osage, mutilating their bodies and scalping them.

The Oklahoma Osage are a nation under siege by the scourge of capital expansion, material gain, and the profit motive that goes back to the founding of the USA.

While some superficial references are made to the so-called Trail of Tears era, which saw Native Americans continuously disrupted by the white movement west following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Grann opts to eschew the more complicated history of a white nation expanding, in order to set up his scene of the crime narrative. The Oklahoma Osage are a nation under siege by the scourge of capital expansion, material gain, and the profit motive that goes back to the founding of the USA. The Constitution was established by property owners, and only reluctantly mediated by the justice implied by the amending Bill of Rights.

Scorsese last directed De Niro in The Irishman (2019) and DiCaprio in Gangs of New York (2002). The two haven’t co-starred since This Boy’s Life (1993), when DiCaprio was a teenager. And this is the first time both have worked together for Scorsese. This is effective ensemble work here. These three principal characters create a complex, triadic, dialectical bond that features themes of criminal loyalty (Hale – Ernest), marital devotion and trust (Ernest – Mollie), redemptive faith in Catholic ethics (Mollie and later Ernest), and the parasitical domination of one tribe over another (whites over Reds).

Such dialectical turmoil is a feature of Scorsese’s work. But in Killers it is not fully fleshed out. The director relies heavily on the interaction of the three main stars to manifest the tensions among these themes. But it is such a simple plot that the dynamic becomes tired, maybe even trite, over three hours. De Niro’s Hale has worked out how to plunder Mollie’s money by getting Ernest to marry her and then wiping out her relatives so that all their oil rights go to her. Hale is poisoning Mollie through Ernest, using him, and in the end he will attempt to control the funds by having Ernest sign them over “voluntarily.”

The depth and variety needed to sustain the motivating forces of the action could have been remedied by the Scorsese who is deeply engaged with questions of faith… We find, though, that Catholicism and its power is buried for some reason in Scorsese’s film.

I think that the depth and variety needed to sustain the motivating forces of the action could have been remedied by the Scorsese who is deeply engaged with questions of faith, who has often depicted the internal struggles with faith, loyalty, and devotion, especially when up against the forces of dark oppression and exploitative domination. Such is the Christian mission, but especially the Catholic way, and Scorsese is a Catholic.

We find, though, that Catholicism and its power is buried for some reason in Scorsese’s film. It’s not completely absent, but viewers may well wonder at the degree of suppression. As mentioned, the director puts the main characters into a dialectical dynamic that is typical of an examination of faith at risk. However, the script plays out formulaically, along conventional lines of evil schemers and white hat rescuers (FBI, Tom White).

Grann describes the kinds of white people drawn to the Osage in Indian Country -—after the discovery of oil — and it is a disturbing picture of fallen humankind:

…the reservation’s tumultuous boomtowns, which had sprung up to house and entertain oil workers—towns like Whizbang, where, it was said, people whizzed all day and banged all night. “All the forces of dissipation and evil are here found,” a U.S. government official reported. “Gambling, drinking, adultery, lying, thieving, murdering.

Though Scorsese does a reasonable job of depicting some of this, its full intensity is missing.

I wonder if viewers would have seen the film differently if they knew that the Osage being depicted were at that time overwhelmingly Catholic (approximately 80%, by one estimate). And that in 1920 (as opposed to today’s more Godless worldview, despite the continued and unresolved turmoil between the three Abrahamic religions), it meant something to be a faithful, perhaps militantly anti-agnostic Catholic — it still meant something in the ’60s, when I was confirmed, and when JFK became the first American Catholic president, worrying many bluebloods who pictured him as a pawn of the Vatican. The Osage of the film had an intimate and, by then, long-standing relationship with Catholic missionaries. According to one account, “Catholic Education Among the Osage,” by Velma Nieberding,

The Osages had lost much. . . by coming into the Indian Territory. They had agreed to sign the treaty with the United States and to sell their lands in Kansas on the express condition that the [Catholics] should accompany them to their new reservation.

They trusted the Catholic mission, which was supportive of their needs, respectful of their customs, and arguably helping them (by converting them) to a more “modern” ritual base. Nieberding paints a picture of how the new faith (cosmology) was absorbed by the Osage:

The Indians ran after [the priest] to have their children baptized; all of them wanted to go to Confession and to attend Mass. They even insisted on the priest going to the cemetery to bless the graves of their dead.

So this din of iniquity all around the Osage gains an important focus if seen through a Catholic lens. Grann tells us of how the Osage wealth was depicted:

The public had become transfixed by the tribe’s prosperity, which belied the images of American Indians that could be traced back to the brutal first contact with whites—the original sin from which the country was born. Reporters tantalized their readers with stories about the “plutocratic Osage” and the “red millionaires,” with their brick-and-terra-cotta mansions and chandeliers, with their diamond rings and fur coats and chauffeured cars. One writer marveled at Osage girls who attended the best boarding schools and wore sumptuous French clothing, as if “une très jolie demoiselle of the Paris boulevards had inadvertently strayed into this little reservation town.”

This prosperity is touted at the film’s onset, but it seems carnivalesque, as though the Osage were being presented as dolls in a playhouse owned by whites, and their dolly obligation was to buy, buy, buy. This is a long way from a heritage of hunting bison on the plains. It’s bizarre, as if Scorsese’s Wolf of Wall Street suddenly popped up here to dance with the other wolves.

Catholicism is introduced early in the film in the first real talk that Mollie and Ernest have in her house at the dinner table. Mollie fears (justifiably) that Ernest is interested in her money as a motive for courting her. But Mollie understands that Ernest is loyal to William Hale (Ernest’s uncle), so she is leery. She is certainly suspicious of Hale. But she likes Ernest. He is fumbly with words, and a human heart seems to beat behind his rough-and-ready demeanor. She wonders about his spiritual life:

Mollie: Are you scared of him?

Ernest: My brother... Who?

Mollie: ...Your uncle.

Ernest isn’t; his uncle is “the nicest man in the world,” he vouches.

Mollie: ...What is your religion?

Ernest: ... I’m Catholic...

Mollie: You don’t come to church.

Ernest: I’ve, yes, I’ve been away. How come you don’t have a husband?

Deflection: She wants to know, How come you don’t have faith? And he wants to know, How come you don’t have a lover? They will become each other's answers. This seems affirmed to her when he shows up at church the next Sunday and side-eyes her (and, later in the scene, she side-eyes him back). Next thing you know, they get married and are having kids, as good Catholics were meant to do. But that’s the extent of Catholicism’s overt role in the film.

Martin Scorsese has directed several films examining overtly religious themes, including Silence (2016) and Last Temptation, in which the struggle of the Catholic faith and ethic is front and center. He is right now working on A Life of Jesus, based on another of Silence author Shusaku Endo’s novels, which he has said will be devoted to a study of the Gospel’s core teachings, with little proselytizing. And we know he’s shown himself to be a master of depicting the excesses of materialism, such as the over-the-top Wolf of Wall Street, which updates worship of the Golden Calf by replacing it with the big testicles of the Wall Street Bull. (Tourists actually kiss them as if they were Blarney stones.) But, in Killers, Scorsese has let the oppositions of faith and materialism escape and go uncommented on. That is a pity, because the film would have been stronger for it.

John Kendall Hawkins is a poet and freelance journalist. He is completing a doctorate that focuses on the future of human consciousness in the Age of AI.